These are the liner notes from the Johannes Kerkorrel compilation album, “Pêrels voor die Swyne”, which was released after his death. The liner notes give a very complete overview of Johannes Kerkorrel’s life and are reproduced in full and unedited by me. It’s a big read, but very worthwhile because you will learn a lot about the life and times of Johnny K.

The liner notes were written by Deon Maas and Janneke Strijdonk.

Ralph John Rabie was born in Johannesburg on 27 March 1960. He went to school in Ermelo and Middelburg and matriculated at the Sasolburg High School. From an early age he wanted to be a singer and often quoted his mother’s Jim Reeves records as well as all the Elvis he heard in the small towns of his youth, to be a big influence. He learnt how to play the piano, taught himself how to write songs at age thirteen and then changed to guitar which he (at that stage) considered to be a more macho instrument.

After obtaining a degree in industrial psychology and journalism at the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education , he relocated to Cape Town in 1981. He graduated with honours in English literature at The University of Cape Town. The next two years were spent in the then compulsory military service and in 1984, he started working as a sub editor at Die Burger.

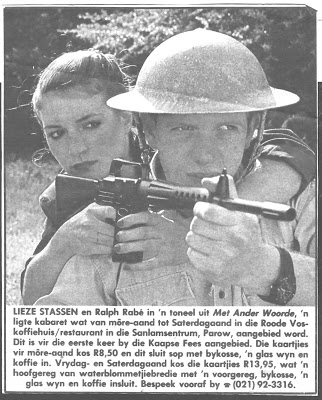

While still working as a journalist, he did his first live gig in 1986 at the Green Room in Cape Town, a highly satirical political cabaret along with writer Elmarie Kitshoff and singer Lieze Stassen.

During that same year he moved back to Johannesburg and landed a job at Rapport. He began collaborating with a group of writers in another political cabaret at the Black Sun in Berea. This cabaret featured songs as ‘Wat ‘n vriend het ons in PW’ and lyrics as ‘O, Kapitaal wat woon in Krygkor…’ sung to the tune of die ‘Onse Vader’.

In 1987, he work-shopped a play, ‘Piekniek by Dingaan’ that won the ‘Pick of the Fringe Award’ at the Grahamstown Festival. The project featured Nataniel, Martinus Basson, Gustav Geldenhuys, Elma van Wyk, Koos Kombuis and Gerrit Schoonhoven. The opening lines of the show, highlighting the paranoia of the time ran ‘In the beginning was the word. And the word was God. And the word became flesh. And the flesh became fear. And the fear became scared.’ The play, sub-titled ‘Kinders van Verwoerd’ rocked the boat at the Arts Council establishment of Capab and he was never asked back for projects by drama departments at the Arts Councils.

It was around this time he adopted the alias Johannes Kerkorrel, which he borrowed from a sign advertising ‘Johannis’ Orrels’.

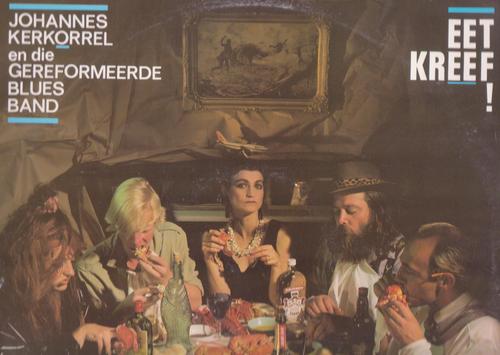

Also in 1987 he started working with Andre Letoit, who consequently became known as Koos Kombuis. They first performed as a duo, then a group of musicians joined them on stage and the band JOHANNES KERKORREL EN DIE GEREFORMEERDE BLUES BAND was born. The GBB consisted of Piet Pers, Hanepoot van Tonder and Willem Moller.

Almost simultaneously Kerkorrel was fired from his job as a journalist at Rapport after being threatened with the wagging finger of PW because of his political activism. From there on, he started making music full time.

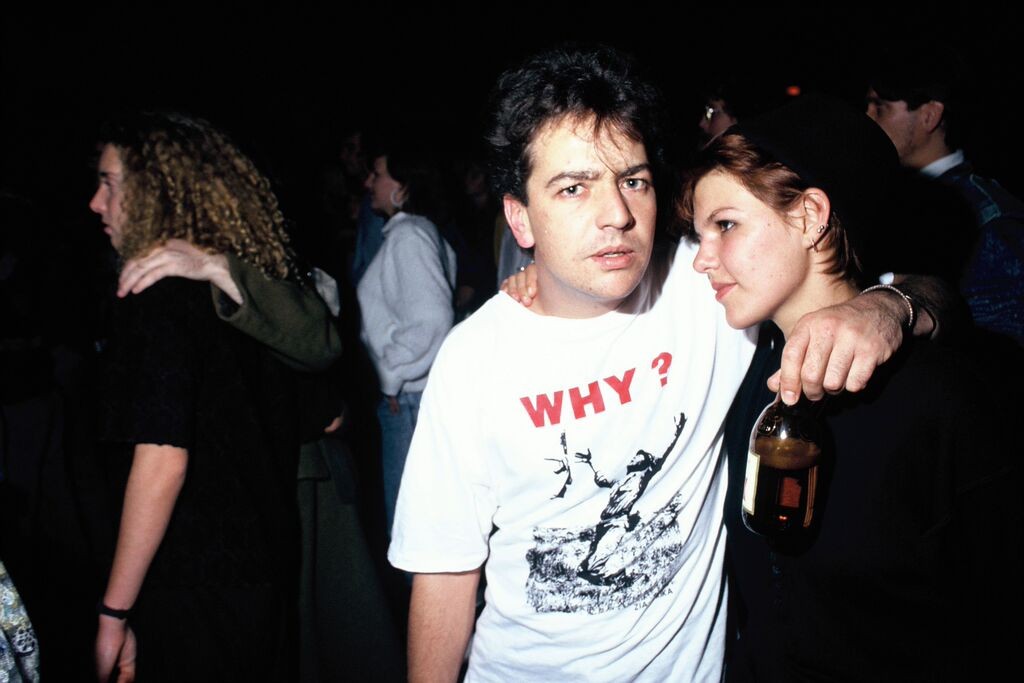

A group of artists, part of a trendy urban young white generation who rebelled against the autocratic dictates of the apartheid state, allied themselves around the GBB. They referred to themselves as a democratic and non-racist collective and organised, in 1988, a concert called ‘Die Eerste Alternatiewe Afrikaans Rock Concert’ in Johannesburg. This concert was a show of solidarity for the liberation of Afrikaans from political fetters and galvanised a lot of support from the underground.

It was held in The Pool Club in downtown Johannesburg, around the corner from Le Club in Market Street. In the audience were large groups of Afrikaners who had become Anglicised because they were ashamed to admit that they spoke the same language as the government. The concert changed people’s lives, sending them in new directions to continue the subversion on a large scale. Some of the most influential Afrikaners in the media today were present at the concert as well as (now) politicians, enterpreneurs and political lawyers. It’s a concert that changed the future and face of Afrikanerdom.

In 1989 the GBB album ‘EET KREEF’ was released and nearly all the songs were banned from airplay by the SABC.

VOELVRY, a nationwide tour of campuses, followed and it unleashed an uproar in Afrikaner circles. The tour featured a.o. the late James Phillips as Bernoldus Niemand and nearly did not go ahead when it became clear that nearly all Broederbond-controlled campuses were paranoid about the concert. The issue of freedom of speech was at stake and tough battles were fought by the students who rebelled against the bans and organised alternative venues so the tour went ahead uninterrupted.

At the University of Stellenbosch, the heartland of Afrikaans, the ban led to one of the biggest mass rallies in the history of campus. Eventually 4000 students attended the concert at Die Drie Gewels, a hotel outside town, not in the least intimidated by the security police filming the audience or the German and Swedish television crews filming the performers. Two days later the Voelvry-concert filled out the 3Arts Theatre in Cape Town, the first time in fifteen years this had happened since the cultural boycot. The tour ended in Windhoek, amidst controversy in the town after somebody pulled out a gun during the gig and ordered the audience ‘to stop smoking pot and bringing their own booze’.

Voelvry relocated to Club Oddysey in the coloured township of Windhoek, where it ended officially.

In 1990 after the banning of Voelvry on Afrikaans campuses nationwide, the banning of his songs on radio and the split of the GBB, Johannes Kerkorrel left for Europe where Eet Kreef had just been released. Initially he stayed with a group of exiles in Amsterdam and met up with artists, actors, conscientious objectors, writers and ANC exiles in the city.

At the same time the song ‘Hillbrow’ from Eet Kreef became a radio-hit in Belgium and people became curious about this ‘white South African’. Consequently he was invited for a solo-tour in Belgium and after numerous interviews with newspapers, magazines, radio and TV, explaining time after time that ‘no, not all white South Africans support apartheid’. Johannes Kerkorrel was the frist white Afrikaans singer who got completely accepted by the media and public.

This then resulted in him being invited to the prestigious Dranouter Festival, where Donovan opened for him and where -to Kerkorrel’s amazement- the audience of 15.000 sang along to his songs. At this festival he shared the stage with the likes of Rory Block, Luka Bloom and Thomas Mapfumo.

But it was not only the Benelux countries that was thrilled by Mnr Kerkorrel. This “alternative Afrikaner” found himself written about in the Washington Post, London Observer, Newsweek, Spin and American Vogue.

Television documentaries about him or the movement were screened in Germany, England, Japan, Sweden, Norway, Switzeland and even PBS in America.

In September 1990 he returned to South Africa to record his second album ‘BLOUDRUK’ and toured the country extensively with ‘Die Blou Aarde Tour’, which ended at the hugely celebratory – Mandela had just been released- Houtstok Festival. Bloudruk was initially recorded by Lloyd Ross for Shifty, his then record company. Tusk Music became interested in Kerkorrrel due to the fact that they were looking for a push into the so called “alternative” Afrikaans market – seeing it as the next big thing. Initially Kerkorrel was very apprehensive but following a series of meetings and the exchange of a rather healthy sum of cash, he made the jump to Tusk. A press release welcoming him to Tusk mentioned the fact that he now shared a record label with Cora Marie. Kerkorrel was not impressed. Contrary to popular belief this turned out to be his biggest selling album ever.

But this also started Kerkorrel’s love/hate relationship with the media. Bloudruk moved away from politics and more into the realm of social commentary. Bloudruk was a wishlist for a new social status quo in South Africa. Even though the album was very commercial in standard pop terms, Kerkorrel’s reputation and his usage of African influences on an Afrikaans album, lead to him being caught in the middle of being too pop for the alternatives and too alternative for pop fans. Even though Vrye Weekblad gave him the cover story, it dedicated a whole page to slagging the record off – including the press release and picture that accompanied it.

The video for Halala Afrika, shot by Hennion Hahn and Grethe Fox was done on such a shoe string budget that the reason he carries a boom box in his hand is because there was no money for a soundsystem loud enough to do long shots with. The shirt was also borrowed. Due to his insistence on doing everything himself, the discrepancies in tracklisting between the back of the CD and the booklet is still there today. For the now famous “blue” pictures done for all the promotion around the album a South African body painting champ was hired and a Canadian photographer, Tara Jang. Kerkorrel’s willingness to go naked ended shortly before he had to take his jockstrap off. The studio where the pictures were taken didn’t have a shower which resulted in him driving home covered in blue paint from head to toe – literally.

In 1992 , as Ralph Rabie, he started to work as the South African correspondent for the Belgian Radio 1 programme ‘Het Einde van de Wereld’, every Sunday untill 2001 he entertained his listeners with his weekly column in which he commented on every thinkable topic under the South African sun.

In 2002, he wrote his last newspaper article for Die Burger on the crying need for environment-friendly housing and the immoral contrasts between the rich and the poor in the Cape. This razor-sharp analysis of present-day South Africa, got to be regarded as Kerkorrel’s political will.

Kerkorrel met Dutch singer Stef Bos in a bar in Antwerp in 1990 and it was the start of a long standing professional and personal friendship. In the beginning of 1993, Stef came to South Africa to write and record with Kerkorrel. The single ‘Awuwa / Zij wil dansen’ (with Tandie Klaasen) was the result and it was released in South Africa and the Benelux. The song became a hit in the Low Countries and Kerkorrel and Bos performed it live with Princesse Mansia M’bila -an authentic princess from Zaire- who took the place of Ms. Klaasen for the overseas tv-programmes.

Later that year the CD ‘BLOUDRUK’ was released in Europe and Kerkorrel was invited back for a tour of Flemish and Dutch Summer Festivals with his Antwerp-based band. This tour proved to be hugely successful and Kerkorrel was to be seen and heard on nearly every radio- and tv programme, and two TV-documentaries were made about him.

From there on Kerkorrel was frequently travelling to and fro and played a.o. the Marlboro Tour circuit in Flanders, ‘De Piano’ on the townsquare of the historical city of Bruges where he played solo at the grand piano (also featured in the line-up that week was Randy Newman) and ‘Boterhammen in het Park’ in the Royal Park in Brussels.

By that time he also started to get invited for special onc-off concerts in Belgium such as a double-concert with singer Wannes Van de Velde in Ghent for the NGO’s and government-representatives at the ‘Nationale Honger Solidariteitsdag’ and the launch of the ‘Vlaams/Zuidafrikaans Intercultuur Fonds’ where he was named Cultural Ambassador.

In 1994, after South Afrca’s first democratic elections, Kerkorrel, the reluctant revolutionary, happy with the changes in the country, said he no longer felt compelled to write about politics. One of his most cherished performances, was at Nelson Mandela’s Presidential Inauguration where he sang ‘Halala Afrika.’

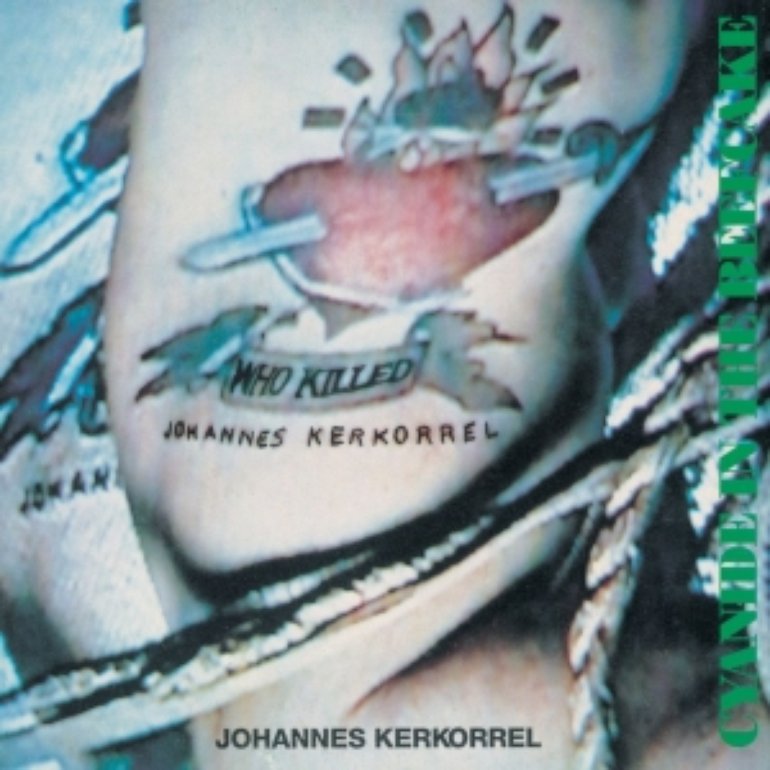

A few months later, his third album ‘CYANIDE IN THE BEEFCAKE’ was released and again he toured South Africa solo and with his band: Mauriz Lotz, Didi Kriel, Andre Abrahamse, Reuben Samuels, McCoy Mrubata and Barry van Zyl, Barry Snyman, Andrew Cleland and Amagugu Akwazulu.

By this time Kerkorrel was living a rock and roll lifestyle. Cyanide in The Beefcake saw him at his most nihilistic, paranoid and decadent. He had the record company kicked out of the recording studio, ran way over budget and walked off stage halfway through his first song at a major media launch. Cyanide was a concious attempt to break Kerkorrel into the English market. Mozambique was originally recorded in Afrikaans, but changed to an English lyric at the last moment. By then a lot of English speaking South Africans were aware of this “alternative Afrikaner” but more people had heard of him than had heard him. The way to break him to English-speaking South Africans and even internationally (outside the Benelux countries) was to have enough English tracks to play on the radio. River of Love was earmarked but was too long and too rock oriented for 5FM’s format at that stage. The help of Gary van Riet was brought in to do a dance mix of the song that would be acceptable to 5FM. Having accomplished this (much to the dismay of Kerkorrel), the single was making healthy headway on the 5FM charts until the latest issue of Playboy came out. It featured an interview with Kerkorrel in which he slagged off dance music and 5FM (especially the jocks). A week later the single had dissapeared off the 5FM playlist. Kerkorrel was never playlisted there ever again, nor did he ever attempt to do another commercially successful English track.

Daar is Geen, the first single off the album was to have a video. Girl about town, Robyn Conway was chosen as director and she decided to shoot the video in the Kalahari. This was before the 5FM debacle and Tusk was still pushing big money into the record. The night before the convoy departed for the Kalahari, Kerkorrel picked up a new lover. At his insistence the lover had to be taken with on the video shoot. By the time the convoy reached the location, Kerkorrel had decided that the new lover was to be both the art director as well as the director of the video. Then it started snowing…in the desert. Needless to say much of the video was finished blue screened in a studio in Johannesburg with stock footage stolen from all over the place.

The cover features the arm of a Tusk sales rep and part time body builder, Clayton Gogle. The “tattoo” was carefully and painstakingly painted by Lukas Luislang erstwhile of Via Afrika, then make-up artist and now also one of those singers in heaven. This was a time when video was becoming accessible to the guy on the street and the whole idea was to create an arty and futuristic cover that deployed modern technology. The press was less impressed and a new photoshoot (the black and white one with the shaven head and the single strand of long hair) had to be done pronto.

Cyanide was written at a time when Kerkorrel had just lost a lover to suicide (the same lover that would later surface during the Koos Prinsloo fracas). It was his first encounter with death. He said subsequently that he wrote Cyanide because he was angry (woedend).

In the same year ‘Cyanide in the Beefcake’ was released in Europe and this time, Kerkorrel went on a tour of the Flemish theatres, which ended at the ‘Nekkanacht’ in the Sportpaleis in Antwerpen where he performed for an audience of 14.000 people. This alongside top Dutch and Flemish bands such as Amsterdam band The Scene, Dutch singer-songwriters Stef Bos and Frank Boeijen and the Flemish superstar Raymond van het Groenewoud.

In 1995 he won the FNB Sama Award for best rock music performance for Cyanide in The Beefcake. At the awards ceremony he performed Waiting for Godot live. ‘Speel my Pop’ a documentary on him made by Ken

Kirsten for SABC 3, featuring three videos from the Cyanide project, won an Artes.

In the same year he played at ‘Les Halles de la Villette’ in Paris, during the ‘L’Afrique du Sud Festival’ a celebration of music from the new South Africa, along with Hugh Masakela, Vusi Mahlasela, Sankomoto, Johnny Clegg, Bayete, etc.

Kerkorrel played the Grahamstown festival regularly as well as the Klein Karoo Kunstefees and the Aardklop Kunstefees, he did regular solo- performances as well as big concerts with his band from the Warehouse Theatre in Windhoek, to Cape Town, Pretoria, Johannesburg, Durban and the Observatory Theatre in Bloemfontein.

One performance that especially touched Kerkorrel was at the inauguration of President Thabo Mbeki, where the 100.000’s strong audience joined him in his songs-much to the amazement of such African

musical luminaries as Papa Wemba and Manou Dibango.

His fourth album ‘GE-TRANS-FOR-MEER’ written while living in Cape Town, saw him recording his own version of the traditional Afrikaans song ‘Al Le Die Berge Nog So Blou’. The show, with the same title, and featuring material from his new album quietly sold out all over South Africa. The CD won two FNB SAMA Awards – one for Best Afrikaans Performance and one for Best Male Vocalist. Ge-Trans-For-Meer was recorded at Marius Brouwer’s Pop Planet studio. It was the last time he collaborated with Did Kriel. At this point Kerkorrel was floating around rather aimlessly, collapsed onstage in Bethlehem and spent a few days in intensive care and accused everybody in the studio of changing the mixes at night when he went home. His record company was only allowed in the studio when he wasn’t there. In one of the biggest ironies in pop history he changed the sex of the person to whom the love was directed in Al Le Die Berge Nog So Blou – turning this FAK song into a gay anthem. Yet this was the song that finally broke him through into the mainstream Afrikaans market. After eight years and four albums, Kerkorrel was finally being accepted in small towns and regional radio.

The CD ‘ TIEN JAAR LATER’, a compilation of his best songs, was released in October 1998 to celebrate Kerkorrel’s ten years on the stage. At this stage Kerkorrel and Gallo (who bought over Tusk) had a huge fallout and with Kerkorrel being at the end of his contract, he decided to move on. After months of checking out other record companies he reappeared at Gallo, wearing a tie and dragging along a new lover. He promptly announced his willingness to resign to Gallo. The new lover was Demetrios Demitriou. Not only would he change Kerkorrel but he would also change Kerkorrel’s relationships to those closest to him. During Kerkorrel’s wild years, the closet confidants he normally had were people he knew the shortest. He would take the advice of a “friend” that he had known for four days over that of someone who had known and worked with him for a long period of time. At one stage there was even a Kerkorrel “support group” where people who actually cared about him would phone each other with “you wouldn’t believe what he did this time” kind of stories. Demetrios changed that. His calmness and spirituality opened a new door for Kerkorrel and helped to mend a lot of broken relationships. They changed urban Johannesburg for rural Eersterivier. Instead of partying Kerkorrel started going to the gym. While Demetrios would cook lunch, Kerkorrel would feed the neighbour’s horse.

After dabbling with other people’s compositions for the first time on Ge-Trans-For-Meer, he tackled Koos du Plessis on ‘JOHANNES SING KOOS DU PLESSIS’. It was again nominated for a FNB SAMA Award. The album was partially recorded in Kerkorrel’s home studio and then completed in Johannesburg. This was the first time he worked with Neal Snyman and it was a relationship that was to span two albums. Now no-one from the “old” days were involved in making his music anymore. Kerkorrel would spend his days in the studio while Demetrios made tea and sat in the sun sketching. When hey did gigs, Demetrios did sound and lighting. Kerkorrel refused to travel anywhere without Demetrios at his side.

He became involved with the prestigious Om Te Breyten project where a wealth of artists each took a Breytenback poem and made a song out of it. The album won an South African Music Award.

His fascination with Breytenbach continued on his next album where he did another Breytenbach poem, Slaap Klein Beminde.

His last album ‘DIE ANDER KANT’ was released in September 2000. During 2000-2001 he toured the country with his show related to this album. Die Ander Kant reflected a new era. It was the first album written in it’s totality in Cape Town in the house where he found peace. The title track reflected how he left the city and it’s craziness behind and he now lives on the other side. At the Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees 2001, his daily performances in ‘De Vlaamse Tent’ were completely sold out, yet the media savaged the album.

In October and November 2001 he at long last toured the Flemish theatres again with his European band ‘De Vlaamse Kerels’ with his longtime friend Rudi Genbrugge, with whom he co-wrote some songs for his Bloudruk album, as the musical director.

He won two Geraas Awards for the album ‘Die Ander Kant’, in Best Pop Album and Best Arranger

categories in January 2002.

In July 2002, he performed solo in London, August sees him invited to the Dranouter festival in Belgium for the third time, unique in the history of this prestigious festival. His concert was an enormous success an plans were made for another theatre-tour with ‘De Vlaamse Kerels’ for 2003.

All through the year he was busy working on his new (unreleased) CD ‘Die Hart is ’n Eensame Jagter’. The show, with the same title, premiered at the KKNK in Oudtshoorn to much acclaim and also ran at the Aardklop Kunstefees in September.

In mid-October he collaborated with Stef Bos, Ray Phiri, Louis Mhlanga and Afrika Mamas in a high profile show for Memisa in the Hague, Holland. It was with this show that Kerkorrel finally made his impact on the Dutch audiences and raving reviews followed.

Johannes Kerkorrel passed away at the age of 42, on 12 November 2002. The country that had alternately loved and loathed, repelled and inspired him, celebrated his life in a wave of tributes. In parliament, the deputy minister of Arts Culture Science & Technology, Bridgette Mabandla said: “… he espoused nationbuilding, tolerance and acceptance of our diversity. His standpoint against the order inspired many people, he will always have a place in the cultural history of South Africa.”

Colleagues and friends spoke and sang at memorial services, held in the Baxter Theatre in Cape Town and MegaMusic in Johannesburg. Amongst them were Lieze Stassen, McCoy Mrubata, Grethe Fox, Valiant Swart, Thandie Klaasen, Amanda Strydom, Laurika Rauch and David Kramer. The message shared was one of friendship and the impact Kerkorrel had on the people close to him and South Africans in general. David Kramer said : “ I remember that I saw him for the first time in 1987 in this same theatre. That day he made me sit up and listen, he did what only the best performers get right: he surprised me. Ralph was not an entertainer, he was an artist. He was true to himself, he had vision and guts.”

Of all the tributes that poured in from around the world, one in particular probably best sums up the feeling of the majority of his fans: ‘I am Eunice Piek from Radio Atlantis in Mamre. You do not know me. Forgive me if I tell you I do not know Ralph Rabie, but I surely know Johannes Kerkorrel. I have never been to Hillbrow, but I know what the streets look like. I have never traveled to Europe, but I know of Europhobia. Forgive me if I speak of Johannes in the present tense. He is my pillar of stength, his music speaks to me. He is a diamond that we must cherish as long as we speak Afrikaans.”

Over the years Kerkorrel matured, became more relaxed and developed a different attitude towards life. Yet there were those who always wanted him to be the angry upstart from Eet Kreef – and publicly criticised him for “selling out”. To Kerkorrel however this was more of a logical progression than selling out. He refered to the “pain of being famous” and wrote a song like Sirkus Dier. He took criticism from the media very personally and tried to explain that his music has moved from the political to the politics of his environment. Six months before his death he became involved in a very nasty and very public scrap with Dagga-Dirk Uys, one of the people involved with the Voelvry movement.

Eventually, on the insistence of Demetrios he walked away from it – unresolved but deeply hurt by all the venom directed at him.

There are a couple of things that has to be remembered about Kerkorrel: One of them is that he never lost his contempt for authority. He felt that the media allowed other people to get away with things but not him. He constantly changed the lyrics of his songs when he performed live to reflect the changing society around him. He wanted to collaborate with Brenda Fassie and Patricia Lewis, Steve Hofmeyr and Yvonne Chaka Chaka but never got around to it.

He hated rugby so much that he threatened to immigrate during the 1995 World Cup Tournament. He hated alcohol and drunk people. He had a phobia about his ears – photgraphers were never allowed to take a picture in which both his ears showed at the same time. He eventually had

them pinned back with disastorous results. He also had a toital obsession with hands…

You can only put off the inevitable for so long, so eventually we have to come to the issue of “Die Hart Is ’n Eensame Jagter” – his last, incomplete and unreleased album. Though he had performed it on stage, it had not been recorded properly and in order to understand the whole woo haa it is perhaps best to look at how Kerkorrel recorded to understand all the arguments that says it should be released or it shouldn’t be released. Firstly it is important to understand that Kerkorrel was a perfectionist. He would record very basic tracks in his studio at home and then send it to Gallo.

Here Deon Maas (and him alone) were allowed to listen to the tracks and send advice back to Eersterivier. When Deon’s portfolio was passed on to Paul de Klerk, they had to get special permission for Paul to listen to Kerkorrel’s demo’s. He would not allow anyone to hear anything that was not finished and to his satisfaction. Die Hart Is ’n eensame Jagter definitely doesn’t fall under the “finished and to his satisfaction” category. He would have hated other people to hear it. It is also not possible to complete it as some have claimed in the media because the separates are not available.

In short Kerkorrel would have hated you for hearing the four tracks on this compilation.

3 comments for “Liner Notes from the Pêrels voor die Swyne compilation album – by Deon Maas & Janneke Strijdonk”